“We need to be remembered. There’s no depiction. There’s nothing about us, [but anyway] we say, all miners are black. We are [all black], till we get showered down there [underground], when we come out of the pit, and then you can see.”

Features

The lost story of Britain’s Black miners

Jimmi Poyser is one of hundreds of Afro-Caribbeans who worked in British coal mines in the decades after the second world war. He and his colleagues’ contribution to Britain’s industrial life has never been recognised in the history books. Not until a unique curation by Norma Gregory, a historian and broadcaster.

Her work led to a major exhibition in 2019 at the National Coal Mining Museum in Yorkshire, UK. The collection of stories, artefacts and photographs is now on the move, due to open in Newcastle at the former Mining Institute, now the Common Room of the Great North in October 2021.

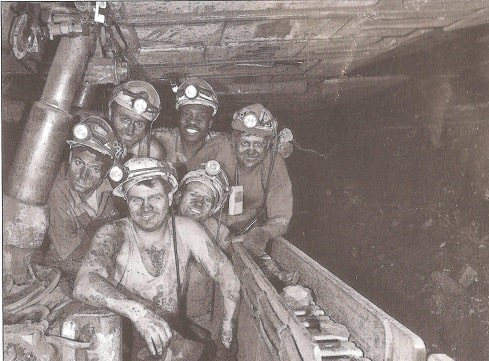

Miners at Calverton Pit. Photograph courtesy of David Bell

Miners at Calverton Pit. Photograph courtesy of David Bell

As Norma will reveal, the project tells of a bigger story; of our post-war past, the rebuilding of Britain, the history of working-class, large scale, industrial employment and of course, the national improvements in health and safety in mining and Black miners’ part in these stories. These are all told through the lens of these amazing men who shared their stories for the public to become aware of their experiences within British coal mining history.

Beginnings

Norma, born in Nottingham in 1969, a former schoolteacher, mentor and since 2013, a director of Nottingham News Centre CIC, a social enterprise specialising in EDI (Equality, Diversity and Inclusion) consultancy, has spent the past eight years gathering oral histories of living miners.

The journey began with her first interviewee, a relative who had worked in the mines in Nottingham for 28 years. Norma says: “He referred me to friends of his and then I started to ask around at local Community Centres, Afro-Caribbean groups, social media groups, and I found a wealth of miners, first mainly in Nottingham then much wider afield and I was really shocked at the scale of these undervalued, stories as national heritage; from diverse communities and other nationalities as well. I thought this was fascinating – there was very little written about it at all.”

From that first spark of curiosity and by not taking no for an answer – other historians initially told her there were ‘no black miners’ – she has interviewed more than 70 miners and logged 250 names in total, including those who she could not speak to directly and those have who have since passed away but are remembered by former colleagues or family members.

Norma Gregory, curator of the project with an image shown at one of the first exhibitions of the Black Miners Museum. Photograph: Norma Gregory

Norma Gregory, curator of the project with an image shown at one of the first exhibitions of the Black Miners Museum. Photograph: Norma Gregory

The Black Miners Museum project focuses on using media including documentary, video, audio, publications, and touring exhibitions to reach people and new audiences. The project also comprises artefacts, such as miners’ lamps, training booklets, photographs, and coal to be used creatively through workshops to engage children in the story of coal.

It has been a project of passion and commitment from the start. Norma’s home served as a temporary museum before she found the funds and space to store items. “At the beginning, [all the items] were in my house, my living room, my bedroom. It was everywhere.” At one stage she even had four tonnes of coal in her shed!

Why were there Black miners?

Many Black miners came from Africa and the Caribbean to work in the UK in the aftermath of the second world war. At this point, nearly 451,000 British people and civilians had been killed and more than 376,000 servicemen wounded. “The government had a shortage of workforce, so they asked, men and families from Commonwealth countries in particular to come and help rebuild Britain,” explains Norma.

After the war, Britain was very poor, living off loans from Canada and America which were running out, while some cities had been bombed and industries mothballed to focus on the war effort. The answer was to rebuild by resurrecting steel, shipbuilding, textiles and manufacturing – only possible through coal. In fact, it was known as King Coal – it made everything possible!

“This coal was used to power factories, stations and heat homes, and families sacrificed. Many men died underground and, on the surface, as well. They died through rock falls, flooding, flying debris, heat, explosions and accidents operating new machinery. A lot of miners that I interviewed now have lung problems or broken bones through working underground and they’re still living with those pains and injuries,” says Norma.

Rupert Meikle, coal miner 1950s. Photograph: Meikle family collection / Black Miners Museum Archives

Rupert Meikle, coal miner 1950s. Photograph: Meikle family collection / Black Miners Museum Archives

So how and why did these men decide to leave their homes to work in the strange, dark, dusty and uncomfortable environment of UK mines? As well as the recruitment drive, there were new laws in place. With the British Nationality Act in 1948 (which confirmed British citizenship for those born in Commonwealth countries), large scale migration from the British Colonies and Commonwealth began, with a steady flow from the arrival of HMT Empire Windrush in 1948 until the early 1960s.

The Black population in the UK grew substantially – from 20,000 pre-war to 1 million by 1969. Mining was a job which promised better opportunities and more money than could be found at home. Norma says: “A lot of men were told about the mines from fathers, brothers, uncles, who were here in the UK already. They went to the coal mines and asked the office, do you have a job?”

Nationalisation and safety

The risks in mines were considerable. But thanks to nationalisation of many industries, including coal, and of course, our health service, welfare and safety improved. Announcing the newly formed National Coal Board on 1 January 1947, Prime Minister Clement Attlee said: "The coal-mines now belong to the nation. [There are now] great possibilities of social advance for the workers."

Norma says changes to safety are evident in the collection: “From 1947 we see miners having specialised equipment, boots with steel toe caps and hi-vis clothing whereas before it was a shirt or jacket or vest – it was very difficult to see other workers underground. So, health and safety changed and saved lives and was very important and still important today, in a lot of hard industries.”

Mines also had to be brought up to speed to make more coal. Production peaked at 228 million tonnes in 1952. Unions saw this as a chance to to improve worker welfare, which it did in that huge modernisation of the mines and investment in machinery took place. As Will Lawther, president of the Coal Workers’ Union said in an address on 24 June, 1946: “We yield to none in our desire to see production reach its utmost limits, for that is the only way to lasting success, improved conditions for the workers, and also the only way to place our country on a sound economic basis.”

However, from the Black Miners Museum we see that there were safety improvements but also archaic, high-risk work and practices. Clyde Forde, an ex-miner from Wales, recalls how he had been trained (training came in under the National Coal Board in 1947) but he still worked with a shovel and pick in cramped conditions.

He says: “In some places, it was like working underneath a table and in other places you needed a ladder. If you were at the [coal] face that had a plough, you were on your hands and knees. The hardest part, in the beginning was that they would not let me do nothing. It was more look and learn, rather than get straight in. Once you knew what to do, they would let you have a go because it was all about safety.”

‘Everything shook’: the life underground

Movingly, the project has had an enormous impact on the miners today, many for whom it was the first time anyone had taken an interest in their experiences. “It’s therapeutic for someone to be asked, ‘how was it?' What was it like?’” says Norma. “Obviously, mental health comes into this as well… Some miners I’ve spoken to, there is sadness even when I interviewed them; some cried because it brought back memories of the past.”

Memories of the dirty, noisy, hot and claustrophobic conditions are brought to life through testaments, like that from Keith Burt, a miner from Yorkshire: “It was bloody frightening. Going down th’ pit wasn’t too bad but going onto a coal face, it were a different experience... Noisy, dusty, weight coming in all th’ time, it was the weight coming on that I had to get used to, it went ‘bump’ and everything shook.”

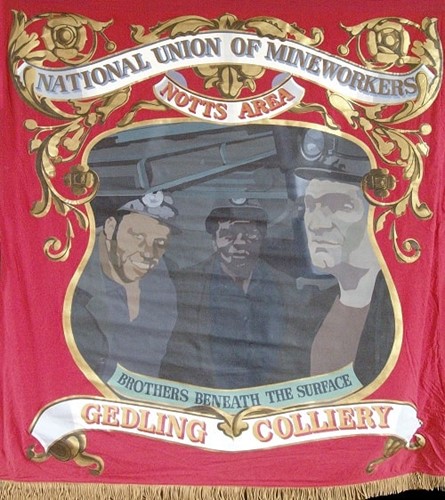

Gedling Colliery banner 'Brothers beneath the surface' slogan. Photograph: Minds2MineEducation

Gedling Colliery banner 'Brothers beneath the surface' slogan. Photograph: Minds2MineEducation

Many Black miners did the most dangerous jobs

The coal face was the most dangerous place to work – it would be around two foot high and men would creep forward, cutting the coal and drilling holes for the shot firers to set and detonate explosives used to blast coal from the seams. “A lot of these miners would age quicker and by fifty-five they’d be old men with walking sticks,” (Working Lives by David Hall.)

Norma discovered Black miners were often given these dangerous jobs. “The majority I’ve interviewed worked on the coal face, which was the hardest job,” she says. Rupert Menzies, a miner recalls: “The foreman and bosses were very aggressive towards blacks in them days, you know, we used to get the bad jobs.”

Brothers beneath the surface

Yet, when it comes to racism in the mines, Norma says the picture is mixed. Yes, racism was rife in Britain at the time and Black miners bore the brunt of this. “Some of them spoke about being told there were no jobs or being questioned in detail about why they wanted the job."

But there was also camaraderie and teamwork. One colliery was ahead of its time. Gedling Colliery, Nottinghamshire, later called the Pit of Nations or International Mine by workers, employed men from more than 30 different nationalities. “On the Gedling colliery banner, it says ‘brothers beneath the surface’ – I thought that was crucial,” says Norma.

“On the surface it was different. Beneath the surface there was support and friendship. They worked together to get the job done.” Still, there was inequality in pay and promotion. Ex-miner, Reverend Kenneth Bailey, says: “The people there were nice but the thing about it is that, as a black man in the arena, with the whites, you were not on the same pay as them. They were getting more money than you was.”

Coal and climate change

Moving on to today, how does a new exhibition on mining fit into our pre-occupation with climate change? Coal is enemy number 1 in 2021 as we gear up for the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow.

But Norma doesn’t shy away from the environmental issues. “Burning coal is a big issue regarding the environment and negative climate change because of carbon dioxide emissions when coal is burned, it produces heat-trapping gases and a consequence of this is global warning and some of the extreme weather conditions we experience across the world today.

The desire to significantly reduce carbon emission risks in existing coal producing countries is really important because it’s affecting the world,” she states. “Coal is part of human existence and the natural world but we have newer technologies. My role is to help realise awareness through education.”

Many of her interviewees suffer from deafness, missing fingers and toes, emphysema, pneumoconiosis (‘black lung’ disease) and silicosis from inhaling large amounts of silica dust found in many types of rocks and soil.

The health, as well as environmental, impacts of mining need to be told, she says, because countries still produce coal, including in Australia where nearly 80 new cases of miners’ lung were recently discovered. “We might not have heavy coal and steel industries in the UK, but they were once there and they’re still around in other countries. China is the biggest producer of coal. India, Australia, Russia, America, you know they’re still burning a lot of coal and making a lot of money from it too. They will have to change for human sustainability. Education is key.”

Mainly, the Black Miners Museum is an extraordinary piece of social history, which would otherwise go unspoken of and the stories fade through time, if not shared and celebrated. “The Black Miners Museum is to make sure this history is part of national industrial history, part of global history,” says Norma.

Mining museums around the country are now diversifying their collections to include the story of Black miners and other diverse mining communities. “I am so proud that we are moving in that direction where the story of British coal mining is being presented in a more realistic way that depicts the contributions and appreciation of different nationalities that worked in British coal mines for the British people and beyond.”

Digging Deep, Coal Miners of African Caribbean Heritage Touring Exhibition 2021 is at the Common Room of the Great North (formerly The Mining Institute) Neville Hall, Westgate Rd, Newcastle UK NE1 1SE, until 1 November 2021.

FEATURES

Sedentary working and how to combat the ‘sitting disease’

By Gavin Bradley, Active Working on 05 April 2024

Prolonged and excessive sitting poses a major risk to our health, but the Get Britain Standing campaign and On Your Feet Britain Day on 25 April are a great way of encouraging workers to sit less and move more.

Company culture and wellbeing: a crucial link

By Bex Moorhouse, Invigorate Spaces on 05 April 2024

Investing in measures to support worker wellbeing will be ineffective unless the company culture genuinely incorporates values like teamwork, involvement, flexibility and innovation.

Office design and culture: happier and healthier staff – or the opposite?

By Guy Osmond, Osmond Ergonomics on 03 April 2024

Applying ergonomic principles to workstation set-ups and ensuring the physical environment supports neurodivergent people are just some of the ways of creating an office where everyone can thrive, but a supportive and positive organisational culture is vital too.