It’s a beautiful day in June and fire safety professional, Russ Timpson should be on holiday, but he’s talking to me. This is because it’s also five years today, on 14 June, since the Grenfell fire exposed severe systemic failings and the industry has a lot to get done.

Features

Can post-Grenfell regulations make tall buildings safe again?

The Building Safety Bill which received Royal Assent on 28 April will come into force in a year to 18 months.

“Every stakeholder from architects, building control, the fire service – they’ve all been found wanting and we have to make significant changes,” says Timpson, who is founder and organiser of the Tall Building Fire Safety Network.

Safety Management wants to understand how the industry is meeting and preparing for its new responsibilities. As we remember Grenfell, are we confident the system which so catastrophically let residents down that night is improving and that it will save lives?

Grenfell fire exposed severe systemic failings in the building sector. Photograph: iStock

Grenfell fire exposed severe systemic failings in the building sector. Photograph: iStock

The challenge

It’s important to realise the problems that led to Grenfell – still being revealed as part of the Inquiry – are not unique to that event but are widespread across the building system. When Dame Judith Hackitt reflected on the findings of her independent review into building and fire safety regulations, Building a Safer Future, published in May 2018, she said: “I have been shocked by some of the practices I have heard about.”

She spoke of confusion about the roles and responsibilities at each stage, regulations undermined by hard-to-follow and excessive guidance: a “whole series of guidance documents which stacked on top of one another would be about 2ft high”.

Beyond this, she found a system driven by profit not safety, creating a rotten culture of risk-taking. Hackitt said: “A cultural and behavioural change is now required across the whole [construction] sector to deliver an effective system that ensures complex buildings are built and maintained so that they are safe for people to live in for many years after the original construction.”

Designing in safety

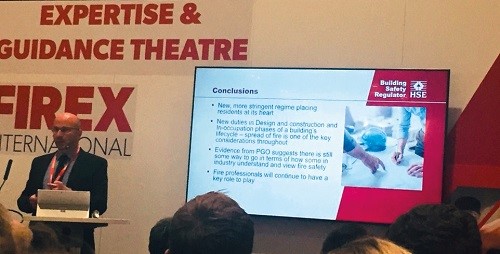

The Building Safety Act seeks to restore a safety-first culture by designing in safety from the start and then monitoring it at every stage. Tim Galloway, HSE’s deputy director of building safety spoke at the recent Firex conference of a “system of integrated parts: the design, maintenance, risk assessment process, ongoing improvements and engagement with residents need to be considered by one accountable person, the building owner with new duties required from others.”

Tim Galloway, HSE’s deputy director of building safety speaking at Firex in May

Tim Galloway, HSE’s deputy director of building safety speaking at Firex in May

The Building Safety Regulator (BSR), which the Act has established and will be embedded within HSE, will oversee the safety and standards of all high-rise residential buildings, that is, buildings over 18 metres tall, or over seven storeys high. Hospitals and care homes will also come into its scope. New projects must submit evidence for the BSR’s scrutiny at three ‘project gateway’ hard stops at planning, pre-construction and pre-handover.

Gateway 1, now up and running, requires the developer to show how safety considerations have been incorporated into design proposals. In many ways this reinstates a lot of the aspiration and hopes that surrounded high-rise social housing in the early days of the ’60s and ’70s.

Paul Dockerill, director of energy & programme management at whg, a social housing provider in Walsall, who has worked with the government’s steering group on building safety, started out as a builder 30 years ago. He recalls: “The traditional approach was for the architect to work for the client to design everything and liaise with the fire service or building control, before procuring a contractor. As we’ve moved to a design and build approach, design teams work for the contractor – in many cases this approach has not worked.”

When post-war architects were building high-rise flats to replace sub-standard Victorian housing, they had safety and resident wellbeing firmly in mind. “In the old days, the standards were so high. And that’s why we’ve got so many wonderful buildings. I think now [with the Building Safety Act] we’ve come round in a circle. I think it will bring back the high standards we need today.”

Slow progress

It’s been nearly one year since Gateway 1 has been in operation. Since August 2021, BSR has received over 1,000 planning applications. According to Galloway, half of them have failed to pass muster, including a quarter which have given rise to ‘serious concern’. Galloway says: “It begs the question whether people know the standards they should be working to or whether they [just don’t] have the competence in design. Maybe organisations know the standards, but don’t apply them.”

There is serious concern that the industry isn’t getting to grips with its new responsibilities. In a progress report on building safety filed earlier this year, Hackitt said that: “We still see an industry that, at best, is in compliance mode rather than a leadership mode.”

A housing development project in London climbs upwards. High rises are still popular, despite the extra regulations that they now face. Photograph: iStock

A housing development project in London climbs upwards. High rises are still popular, despite the extra regulations that they now face. Photograph: iStock

But there is hope that these leaders are influencing the culture, by sharing their best practice examples. Dockerill chairs the NHF Building Safety National Group, which was formed to report and work with the government on progress made towards achieving culture change in the built environment industry. He tells me about an innovative project they have developed to meet the ‘safety case’ part of Building Act’s new duties.

The role of the safety case

The safety case is like a blueprint for everything to do with fire risk management and is meant to be added to throughout the building’s lifetime, reflecting for example, information relating to maintenance and refurbishment.

Dockerill and his team decided that a paper safety case would not be usable enough: “We did some early work around what does technology look like? Is it loads of folders and a cabinet with all the information in? No.” They settled on digital twin technology called TwinnedIt which took two years of research and development to produce.

It visualises in a 3D model the building’s safety and fire risk information via an interactive app. The main point of it is that it’s quick and accessible. “When you read the story of the way the fire had to be tackled at Grenfell you can appreciate why the fire service had many challenges to consider. When they turned up they had no information on the cladding material or how it would perform in the event of a fire,” says Dockerill. “So they had a very unfair chance of trying to save lives.” The app can be used by the fire services on their way to a building: “They are making decisions already [en route] and thinking, right? What have we got? Minutes are all lost because of [not having] that information.”

Paul Dockerill: "The Building Safety Act will bring back the high standards we need."

Paul Dockerill: "The Building Safety Act will bring back the high standards we need."

whg’s approach to the Building Safety Case should be signed off by the BSR in July and then Dockerill wants to collaborate with as many other social housing providers as possible to share it. “We’re not saying this is the solution. We’re just saying this is the progress we’re making and if that helps you, it helps everyone.”

Dockerill does echo Hackitt’s concerns though, that not all organisations are yet prepared to invest time and money into fire safety.

“It is unclear how many aren’t making progress and the reasons they are not. Is it finance, resource, decision process or a lack of clarity in what to do? We need to understand this clearly. If you’re the landlord you’re accountable, nobody else.”

Guidance is needed

Steffan Groch, partner regulatory, compliance and investigations at DWF Law LLP, says that more guidance from government is needed. “I think there is an air of frustration amongst the construction industry that more is not being done to support them in introducing and understanding the changes.” He thinks that the Act’s long implementation period means that “developers are sleep walking towards [the changes] and not being given the right messaging about what they need to do to comply”.

A competency gap

It hasn’t helped that since enacting the Building Safety Bill some of the key points in it that had excited the industry have been removed. The major one for the industry, is the scrapping of the requirement for the accountable person (the landlord, who could be an individual or corporate body) to appoint a building safety manager for each higher-risk building to undertake the many new legal duties, including maintaining the fire safety cases.

Timpson tells me he had been gearing the industry up to appoint BSMs for the past 18 months: “I’ve been saying, ‘great we’re making a huge step forward’, we’re following the example of other countries for tall buildings, in that they have dedicated person to focus on fire and building safety.”

It would have helped plug a hole, he says, because it would have insisted on recruiting people with expertise and competence in fire safety, a key problem that led to some of the lethal decisions that were made and approved in Grenfell. “There’s a huge competency gap in the market for fire safety managers. We’ve got people running buildings out there who in my opinion are wholly incompetent to do it,” says Timpson.

Without a legal requirement for the role, the tasks of the BSM are likely to be spread around people in a department, or will be given to safety managers to do. It’s concerning because in Grenfell, it was revealed that the building control manager was unable to do his job properly because of cuts to his team.

Will we be able to prevent another tragedy like Grenfell? Photograph: iStock

Will we be able to prevent another tragedy like Grenfell? Photograph: iStock

He told the Inquiry he was working on up to 130 jobs at one time. Dockerill says: “I think we have to be careful – there may be models where you can share those responsibilities without the Building Safety Manager, but I think you do need that overall accountable person for the building that brings all things, all responsibilities together.” At whg they have pressed on ahead and hired two full time BSMs.

Resistance to change?

The Act isn’t the full picture – secondary legislation is being developed to support it. In May, the Home Office said it has decided it is not ‘proportionate or practical’ to require the building owner to develop personal fire evacuation plans for disabled people. Watering down of requirements at this early stage is sending the wrong message to the industry, says Dockerill. “The sector isn’t clear about what it has to do and what it needs to do. There is the danger that we will revert back to what we were doing before, whereas what we should be seeing is a complete culture change where resident safety is embedded in everything we do.”

On the positive, Timpson says health and safety professionals, often the Cinderellas of the business, have more leverage for investment into their work and the ear of the board. “Normal health and safety risks don’t get that high on the risk register generally [the register of material risks to the business which companies are legally required to identify, monitor and manage]. But if your prestigious residential development burns to the ground then that probably will. You may go out of business. My logic is that the safety manager with the fire safety brief is the custodian of one of the main corporate risks in the business.” Safety managers who can underline that fire is a top risk on the commercial risk register will have a ‘compelling message’ for boards.

Role of the BSR

The BSR will enforce standards. By 2024, it will call in buildings for assessment and issue building certificates as part of Gateways 2 and 3. New legislation could result in prosecution and criminal sanctions if an adequate ‘safety case’ is not submitted, or improvement notices are ignored. Timpson says: “I sincerely hope the [BSR] will be effective and bring real change. But let’s wait and see.” In a political climate of cutting health and safety regulations to ‘help’ business, we don’t know how much funding will be allocated to the new regulator.

“The [BSR] has a huge task on its hands – it’s not locking the stable door it’s trying to round up a whole herd of horses and get them back in again. It’s going to take some money, some cost and there’s going to be massive push back.”

It’s easy to feel that the weight of the Act, like a judge’s gavel, has put a close to the matter for building safety and that we now have the solutions. But speaking to these voices in the thick of things in the high-rise building sector, we realise that the new regime is only getting started.

One final question and the only real one to ask on the anniversary day of Grenfell: will we prevent another tragedy? Powerful forces of profit are hard to quench, but there are signs things are changing. Plans for a 51-storey London tower were put on hold earlier this year after distressed constituents and fire safety professionals branded the project “madness”. It featured a single staircase, a factor that in Grenfell made it hard for people to evacuate safely. “At Firex, international delegates were shocked that we allow single staircases in Britain,” says Timpson. But since the project was pulled a “number of developers are starting to reflect”.

If the industry can get behind the changes in the Act, then there’s no reason why high rises can’t be safe and happy communities once more. As Dockerill says: “High rises are not the issue – it’s what we’ve done to the buildings since they were constructed.”

For more on building safety reforms, see HSE's website

FEATURES

Sedentary working and how to combat the ‘sitting disease’

By Gavin Bradley, Active Working on 05 April 2024

Prolonged and excessive sitting poses a major risk to our health, but the Get Britain Standing campaign and On Your Feet Britain Day on 25 April are a great way of encouraging workers to sit less and move more.

Company culture and wellbeing: a crucial link

By Bex Moorhouse, Invigorate Spaces on 05 April 2024

Investing in measures to support worker wellbeing will be ineffective unless the company culture genuinely incorporates values like teamwork, involvement, flexibility and innovation.

Office design and culture: happier and healthier staff – or the opposite?

By Guy Osmond, Osmond Ergonomics on 03 April 2024

Applying ergonomic principles to workstation set-ups and ensuring the physical environment supports neurodivergent people are just some of the ways of creating an office where everyone can thrive, but a supportive and positive organisational culture is vital too.