AI is already being widely used to protect people’s health and safety at work, but there’s a danger the data being harvested could be used in negative ways, such as pervasive monitoring of employees’ work rates and performance.

Features

Artificial intelligence: the benefits and dangers of data

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) has been cast as a major opportunity to improve outcomes in health, safety and wellbeing. It’s hard to argue against the benefits where a person can be outperformed by a machine, where the ‘always-on’ presence of automated monitoring can outlast the patience and persistence of any observer, and where robots can go safely where humans fear to tread.

AI can recognise patterns in information that mere mortals would never see – for example, allowing managers to trace the root cause of a health and safety failing down to a specific location, hazard or individual. It can also make recommendations on the best course of action. In the sphere of mixed reality, overlaying digital information onto a headset with a camera feed can not only guide someone to carry out a task safely first time, it can also help to train them both in advance and on the job.

David Sharp, Founder and CEO at International Workplace

David Sharp, Founder and CEO at International Workplace

While the benefits of AI are undeniable, the costs and risks are often overlooked. In this article I want to focus on just one of them – ‘datafication’.

Things are certainly happening quickly. In 2015, Stephen Hawking wrote an open letter cautioning of the potential pitfalls if the risks of AI development are not properly managed.

Speaking in China two years ago, Elon Musk warned of a “potential danger to the public”, as AI researchers underestimate the speed at which technologies are developing and are increasingly losing control. Musk’s company Neuralink is currently working on an interface to connect the human brain with a computer, something he describes as “consensual telepathy”. The talk is of ‘smart technology’. But how smart is it? And who is it smart for?

None of the ‘smart’ processing power of AI can be harnessed without data – as Michael Dell (founder and CEO of Dell Technologies) famously said: “AI is your rocket ship, and data is the fuel.” AI needs huge volumes of data to be able to look for patterns, suggest recommendations and make predictions. There are two ways to access this data: scraping it from publicly available sources, as well as generating it from users. Both are forms of datafication – an attempt to transform human behaviour into data – neither of which is neutral.

User-generated data is derived from what is effectively surveillance, which could involve anything from CCTV footage to tracking Google search behaviour. Photograph: iStock

User-generated data is derived from what is effectively surveillance, which could involve anything from CCTV footage to tracking Google search behaviour. Photograph: iStock

Data scraped from the internet is dominated by the ‘Global North’: wealthy, globally dominant western countries. It comes with norms, assumptions and prejudices baked in, but which might appear invisible to someone (or to an AI) based in those countries. User-generated data is derived from what is effectively surveillance, which could involve anything from CCTV footage to tracking Google search behaviour to someone logging workouts on their fitness tracker.

How smart is it?

Unlike humans, artificial intelligence doesn’t actually understand the data it’s processing, which makes it potentially fragile. Without understanding the content of the data, it is simply looking for, and learning from, patterns in the data. It doesn’t have what humans would call ‘common sense’ to understand when correlations between two sets of data are obviously spurious.

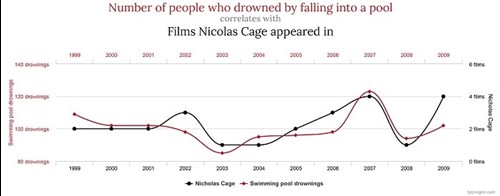

With apologies for the incongruity of the following example, the figure below shows the correlation between the number of people in the US who drowned by falling into a pool, and the number of films that Hollywood actor Nicolas Cage appeared in.

Source: bit.ly/3Se2w5c, Spurious Correlations, Tyler Vigen, tylervigen.com/spurious-correlations

Source: bit.ly/3Se2w5c, Spurious Correlations, Tyler Vigen, tylervigen.com/spurious-correlations

For the 11-year period from 1999 through to 2009, there is an uncanny correlation between the number of people who drowned falling in a pool, and the number of films Nicolas Cage appeared in. The patterns match. But is there causation? Did those 120 people drown in 2009 because Nicolas Cage made those movies? Did Nicolas Cage make those movies because that record number of people died?

A human would know there is obviously no causal link between these two datasets. But an AI would not. It doesn’t know what pools are, or people are, or what films are, or who Nicolas Cage is. It would only know a causal link was highly unlikely if it had masses of additional data to put such a ridiculous conclusion into context. Should something so fragile be relied upon for safety-critical applications? Or should we be looking to generate more data to make it more robust?

Who is it smart for?

As we’ve seen, data that was previously invisible – ‘exhaust data’ as it is known – has suddenly not only become visible through pattern recognition, but when aggregated, has also become extremely valuable.

Let’s apply this to a surveillance system that processes real time data from worker-wearable devices to monitor and promote safe working on a construction site.

The benefits of wearables have been identified as part of the ‘Construction 4.0’ agenda to ‘embrace digitalisation and modern, smart technology’. They can alert workers to the presence of colleagues or specific hazards, control access to certain equipment and even recognise fatigue before workers do themselves.

Pervasive monitoring and target setting technologies are associated with pronounced negative impacts on mental and physical wellbeing. Photograph: iStock

Pervasive monitoring and target setting technologies are associated with pronounced negative impacts on mental and physical wellbeing. Photograph: iStock

But by capturing data from wearables the AI is also given access to a huge range of other – exhaust – data, that may either be private (such as whether you are happy or not) or have little relevance to worker health, safety and wellbeing.

Rather than benefiting workers, the risk is of exploiting them, with data being used to create operational efficiencies and optimise business processes.

This is not an outlandish claim. A report by the UK All-Party Group on the Future of Work in November 2021 concluded that the potential of AI to generate good outcomes for workers is “not currently being materialised”. Instead, it notes, “a growing body of evidence points to significant negative impacts on the conditions and quality of work across the country.

Pervasive monitoring and target setting technologies, in particular, are associated with pronounced negative impacts on mental and physical wellbeing as workers experience the extreme pressure of constant, real-time micro-management and automated assessment.”

As Fred Sherratt asks in a new book on construction safety, whose interests are really being served by workers’ growing use of wearables? Where technology effectively “allows employers to ‘read workers’ minds’, discerning whether they are happy, sad, active, relaxed, creative, and even determining their personality”, then controls should be introduced, argues academic Adrián Todolí-Signes.

This is just one, narrow use case of AI in the occupational health, safety and wellbeing sector, which I hope illustrates the need to ask whether smart technology creates smart outcomes for workers. The ethical debate is much wider, considering more broadly what AI will mean for jobs and human autonomy, and the colossal impact that new technologies wreak on the earth’s natural resources and climate.

Smart technologies bring benefits. Using them should not be a no-brainer.

David Sharp is founder and CEO of learning provider International Workplace and is currently studying a Masters in AI Ethics and Society at the University of Cambridge, run by the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence. Contact him at: internationalworkplace.com

FEATURES

Sedentary working and how to combat the ‘sitting disease’

By Gavin Bradley, Active Working on 05 April 2024

Prolonged and excessive sitting poses a major risk to our health, but the Get Britain Standing campaign and On Your Feet Britain Day on 25 April are a great way of encouraging workers to sit less and move more.

Company culture and wellbeing: a crucial link

By Bex Moorhouse, Invigorate Spaces on 05 April 2024

Investing in measures to support worker wellbeing will be ineffective unless the company culture genuinely incorporates values like teamwork, involvement, flexibility and innovation.

Office design and culture: happier and healthier staff – or the opposite?

By Guy Osmond, Osmond Ergonomics on 03 April 2024

Applying ergonomic principles to workstation set-ups and ensuring the physical environment supports neurodivergent people are just some of the ways of creating an office where everyone can thrive, but a supportive and positive organisational culture is vital too.